The Zoom Film Blog.

Monday, 25 January 2016

Animated Emotional Chart

A chart of how different animated shows handle emotional scenes. Not a comment on how well these shows handle said scenes.

I hope this helps you think a little bit differently about animated drama and how different shows handle themselves.

CLICK TO ENLARGE.

By Jack D. Phillips

Friday, 15 January 2016

Coursework Essay: Film History

Analyse the use of mise-en-scene in TWO of the essential film texts. How do the meanings generated by the mise-en-scene contribute to the viewer’s understanding of the film’s narrative content?

Mise-en-scene is one of the most important and universal aspects of filmmaking. The use of the properties in front of a camera in any film contributes greatly to the overall understanding that the audience has of the film itself. To analyse the impact that effective mise-en-scene can have on a film I will be looking at Taxi driver (1976, Martin Scorsese) and Fargo (1996, Joel and Ethan Coen) as examples.

Martin Scorsese’s film Taxi Driver is often cited as one of the most important films made during the period known as ‘New Hollywood’. This period allowed smaller American filmmakers to show environments and situations previously deemed unsavoury by the Hollywood hegemony. The environment of the film reflects this embarrassment of the darker side of America, set in the dark and dingy slums of lower New York.

The shot above is from the film’s opening sequence and is a great example of how the world of the film looks. This is not a harmonious Hollywood film set, this is a chaotic and decaying New York wasteland. The low lighting reflects the dark and at times disturbing nature of the narrative that is about to unfold, and the stream of water resembles an archway, an entrance that the main character (Travis Bickle) is traveling through. This is not the world that Hollywood has led the viewer to believe is reality, this is a far more horrifying and violent world of darkness. Bickle, despite being a repulsive and terrifying character, also acts as the audience’s proxy in this sense. He frequents porno theatres and when he finally gets a chance to form a romantic connection it is the only place he thinks to take his date. His actions are entirely based and informed by what he sees on the big screen, similar to how the audience’s expectations had been preset by decades of Hollywood cinema.

There are two characteristics of the mise-en-scene that are common in almost every scene of Taxi Driver. Those being filth and darkness. Many scenes share both, notably the key montage sequences of Bickle driving through the streets in his taxi, as seen in the still above. The all encompassing nature of these common elements reveal the mise-en-scene’s purpose. The audience is being asked to enter Bickle’s mind. As a character he is warped, isolated from society and has a dark lust for violence. The mise-en-scene acts as both an extension of his mind and as the possible reason for his alienation. A dilapidated and run-down society that he is prepared to give up on.

When compared to the confined and dingy streets that Taxi Driver occupies, Fargo features far more sparse and pleasant mise-en-scene. The film is set in the American Mid-west and takes advantage of the areas wide open and featureless snowy plains to create a sense of loneliness and as a comment on the noir genre.

As a neo-noir, Fargo subverts and builds upon many of the conventions established by conventional noirs, this subversion is done largely through the mise-en-scene. Classic noirs, such as Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder), were almost universally set in Los Angeles and were known for their use of enclosed indoor environments and intense expressionistic shadows. By setting the film in the Mid-west and making use of a brightly lit and tranquil environment the film subverts the very genre that it belongs to and, much like Taxi Driver, creates commentary on the Golden age of Hollywood.

Aside from commenting on the history of American cinema, the mise-en-scene of these films also affect the audience's perception of the characters. In Taxi Driver his unassuming Taxi acts as an extension of himself, as he prowls through the filthy New York streets. In contrast, scenes featuring the character Betsy (the object of Travis’ obsessions) are set in far more civilised and clean parts of the city and are considerably more brightly lit.

Travis is horribly out of place in Betsy’s world, sticking out from the clean and well kept surroundings in images such as the one above. However in the aforementioned scene at Travis’s porno theatre, Betsy is equally out of place. The film, through the use of its production design and the presentation of it’s characters, is making a comment on the dual nature of New York city, both psychologically and physically.

Fargo also uses mise-en-scene to demonstrate character, although in a more subtle and less noticeable fashion. Marge Gunderson’s home in Fargo, which she shares with her husband Norm acts as a representation of their life and relationship together and it does so through a very subtle use of the cinematography and production design. In the shot above (the final shot of the entire film), the tight angle demonstrates the closeness of their bond, with the slow zoom implying that their relationship will only get stronger with the coming of their first child. The production design is humble and not ostentatious in the least, reflecting the hard-working and humble personality the Marge has demonstrated throughout the preceding events. Even the lighting is humble, appearing to be coming from a out of shot lamp ather than being professionally set up. In an almost ironic outcome, the Coen Brothers were able to get across large and fairly deep ideas about the two character’s and their relationship to each other by setting a scene as simply as possible.

This is not just an example of mise-en-scene contributing to characterisation, but also mise-en-scene affecting how the audience perceives the themes and ideological content of a film. Fargo is a film that harshly criticizes and condemns notions of greed and ruthless ambition, in favour of the humble honesty that characterises the people of the American Mid-west. By ending the film on such a simple and comforting note, with the mise-en-scene feeding this feeling of contentment and harmony, the film's overall theme is tied up conclusively through the mise-en-scene. The film is filled with numerous other examples of this subtle relationship building through production design as seen in the still below of Marge and Norm eating a relaxed breakfast before Marge embarks on a very gruesome investigation. The tranquility of this scene demonstrates how different Marge is from the vile characters we have been following up to this point and how at peace she is with her surroundings.

Colour is also a fairly important factor within mise-en-scene, and Fargo uses the white to great effect throughout the narrative. The desolate snowy plains that the film largely occupies is the home of various gruesome crimes and criminal misdeeds. The scene pictured above features the character Carl hiding some stolen money in the snow. Here the all encompassing and featureless white of the background evokes the inherent purity of the setting, which is being corrupted by the red and bloody form of Carl. The blankness forces the audience to focus on Carl and his actions, blocking out all distractions from the pivotal scene that is taking place. Finally, in terms of narrative the blank wasteland of white confirms that after Carl leaves, the money will be lost for all time, hidden by miles and miles of snowy wastes. Carl dies in a scene following this and so the audience knows that this money was likely never found.

The Coen brothers are fairly well known for their delicate and precise use of colour throughout their other films, such as Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2013) which uses a retro-inspired washed out palette. This was used to evoke the distant nostalgia of the early 1960’s. Thier previous film O’ Brother Where art thou? (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2000) used extensive digital to replicate the sepia tones associated with the art produced during the American Depression. Overall the Coen’s are an excellent example of how to use colour and overall aesthetics to immerse the audience in a specific time period, further engaging them with the narrative.

Mise-en-scene does not simply refer to environment, it also applies to a character's makeup and costume. Suffice to say that the way a character is made to look heavily influences what we think about them. Travis Bickle for instance undergoes an extreme visual change throughout the film, going from appearing as an unassuming everyday man to a deranged punk-inspired vigilante. By externalising the characters change and development the audience is made to absorb the information visually, allowing the ideas to be better integrated into the themes of the film on the whole, and making the character more memorable and distinct to the viewer.

Fargo makes even more frequent use of costume and makeup for it’s characters. Carl becomes more frantic and bloody as the film goes on, getting assaulted and shot before eventually being killed in the most gruesome way imaginable. The blood seen in the still above demonstrates this. Not only does this show the increasing danger of the situation for Carl, but it also shows his inner selfishness and rabid animalistic brutality coming to the surface.

Margie is also a character who is heavily affected by mise-en-scene. She is heavily pregnant throughout most of the film, and yet wears a police uniform at all times- a traditional symbol of masculinity. This not only subverts outdated views on masculinity, but pushes many of the ideological ideas that the Coens explore with this film. Marge is a nurturing and wholly positive figure, she is the person that the Coens wish represented law enforcement in America.

By including ideas of the films narrative into the mise-en-scene, the filmmaker allows for the story to go beyond dialogue and action. Film is a medium best understood visually, and so including ideas such as foreshadowing and character development into the visuals increases audience involvement. It is more engaging to have the viewer look and understand how a character is feeling from what is around them than by being told through dialogue.

The narrative of Fargo ends with Margie capturing the surviving member of the crime duo and taking him into custody. In their only scene together the Coens film them separated by a police grate. This informs the audience of their ideological separation far more engagingly than if the characters discussed their difference. The only lines delivered by Marge are a simple lamentation about greed, this does not take more than three or four lines. Most of the weight of this scene comes from Francis Mcdormand’s face and the humility of her environment and dress, which echoes the honesty goodness she represents.

In conclusion, mise-en-scene is possibly the most important and useful way of engaging with an audience and allowing them to understand the film’s narrative. What the audience sees in front of them can tell them so much more than some lines of dialogue, and the best visual storytellers know this. Possibly the ultimate testament to the importance of mise-en-scene is the French New Wave. During this explosive period of filmmaking, directors were not credited as directors, they were credited for mise-en-scene, for instance in the film The 400 Blows (1959, Francois Truffaut). Mise-en-scene, represents filmmaking in it’s purest form.

By Jack D. Phillips

Coursework Essay: Reading Visual Culture

I just spent the last few weeks working on some really boring coursework essays. In order to make it seem more worthwhile I have decided to upload them to the blog.

Enjoy I guess.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Enjoy I guess.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Discuss the concept of narrative closure in relation to TWO of the essential film or television texts. How does closure-or a lack of closure-affect the viewer’s reading of the texts?

Narrative storytelling has been the dominant storytelling format in popular cinema since the advent of linear editing at the dawn of the 20th century. Since then, the subject of narrative closure has been a significant point of artistic discussion and debate within the cinematic community. In this essay I will be looking at a tentpole release from the golden age of Hollywood narrative film, The Wizard of Oz (1939, Victor Flemming) and an independent post-modern film from the late 1990’s, The Usual Suspects (1995, Bryan Singer).

When looking at the nature of narrative cinema in American cinema the historical context is worth noting. At the time of Oz’s release Hollywood has a very rigid and tightly controlled storytelling structure that was obeyed by almost filmmaker working within the studio system. Every mainstream release had to have a happy ending, and simple narrative conventions were strictly abided to. Therefore, the very neatly resolved closed ending of Oz is typical of the period it was made and released in.

Conversely, Suspects was released during something of a small boom in American independent cinema (following the rise of filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino) and following the birth of an artistic movement known as postmodernism. This movement revolved around the reexamination and subversion of previously established tropes and cliches, in this case narrative tropes and cliches. As such, the far wilder and less conclusive ending of Suspects would have been impossible at the time of Oz’s release.

Due to the more restrictive nature of the time Oz was given a very conclusive closed ending. This brings the film in line with the traditional three act narrative structure that popular cinema was slave to at the time. Rather ironically however, the conclusive nature of this ending is something that has become a source of criticism towards the film from it’s own fans. Many view this ending as being untrue to the true message of the film, one of freedom and individuality. Furthermore, the idea that Oz was little more than a dream (as this ending claims that it was) is seen as a contrived way to wrap up the narrative without addressing the core themes of the film properly.

The Wizard of Oz is a film that has been adopted and treasured by many minority groups, such as immigrants and homosexuals. For these oppressed groups, the films messages of freedom, escape and bravery are taken very much to heart. Dorothy herself, a lonely but strong willed child exploring a bright and mysterious new world, has become an iconic figure in such groups. The ending however sticks sourly in the throats of many of these fans, as it instead backs away from the films bold and inflammatory ideals in favour of a highly conservative ‘There’s no place like home’ message that doesn’t seem to blend properly.

Oz has often been cited as one of the most important films of the Hollywood golden age, and along with several minority groups, has been a source of inspiration for filmmakers since its release. One of the reasons for this is the structure of its narrative, which takes the episodic structure of the source novel and transforms it into an impeccably tight three act structure. It has been posed by many that this structure is an excellent example of the benefits of this structure, and the film has become one of the fundamental models for the fantasy genre. The narrative is clear, easy to follow and conclusive in all ways, and this extends to the ending.

Despite the many grievances that fans and critics alike have about this ending, it is still as influential as any other aspect of the film. The idea of ending a story with and it was all just a dream, has become a constantly repeating cliche, particularly in family-friendly fantasy films. This type of ending is popular for several reasons; firstly it is simple and conclusive, wrapping up all loose ends as tightly as possible. Secondly it is very easy to pull of, and does not require a lot of time to come up with. And finally, it is a fairly comforting ending for kids, validating ideas such as imagination and dreams. However dream endings have been vastly parodied and criticised for all the same reasons. They are seen as lazy, a way for writers to end their stories without consequences or any kind of depth, and are the epitome of audience passivity. All of these criticisms have been labeled towards Oz and are an extension of the criticism given to many closed ended narratives. Furthermore, quickly ending a story with a character waking up from a dream does a disservice to dreams as a thematic device. The television series Cowboy Bebop (Hajime Yatate, 1998-1999) uses themes of dreams to mysterious and unconventional effect, and actually uses dreams to end on a highly inconclusive and ambiguous note.

Overall, despite the simple and narratively satisfying nature of the film’s ending, in Oz’s case a more open and ambiguous ending would probably have done more to complete the film’s themes and ideas. This ending, as are sadly many of the time, an example of the studio hegemony favouring the safer and more traditional style of narrative over what actually serves the film better. A very reductive and conservative outlook towards a very adventurous and progressively minded film.

When creating Suspects, director Bryan Singer did not have to worry about these narrative restrictions. The film was made at the height of the post-modernist movement in American independent cinema, spearheaded by directors such as Quentin Tarantino and Jim Jarmusch. As such he was able to construct a film entirely around a non-conclusive cliffhanger of an ending.

The final scene of Suspects does not answer many of the questions raised in the preceding narrative. In fact it raises several new questions and throws out a lot of what the audience was made to believe was fact. Inconclusive and open endings have existed for a long time, however this was one of the first major examples of a film untethering all we have seen before from reality and bringing the entire plot into question. What was real? Who can we trust? These answers are not only not given, they are made basically impossible to answer.

This ending also goes against many of the conventions of the crime and mystery genres, in many ways an example of a genre which frequently misleads and engages with the audience. In any kind of mystery or crime film, the viewer is asked to keep track of things themselves and figure mysteries before the narrative reveals the answer, the concept of a whodunit is fairly popular in cinema. Suspects goes one step further however, it’s narrative never reveals the answer. So the viewer is kept in an eternal state of anticipation and confusion. Classic crime-noirs such as Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) will happily mislead and misdirect the viewer, however these films always ended mostly conclusively, with the motives of the characters fully figured out and justice being served. This is not the case with Suspects, a film that only compounds upon its own mysteries in the final scene.

The effect that an ending such as Suspect’s can have upon the audience cannot be overstated. The film has become something of a pop-culture touchstone precisely due to the impact that this ending had upon viewers. In the case of this film, the ending gives the narrative extreme longevity, as fans return time and time again to try and decipher the film’s complicated knot of a plot and pick up on the clues that lead to the bombshell of an ending. There are several other examples of popular films that have become iconic due to their inconclusive twist endings, including Seven (David Fincher, 1995) and The Sixth Sense (1999, M. Night Shyamalan). To put it simply, filmgoers love to enjoy a puzzle that they cannot solve, a mystery that the can pour over without ever getting a complete answer. I do not think that there is much of a coincidence that the two films I just mentioned stand alongside Suspects as some of the most popular and beloved American films of the 1990’s. A powerful enigmatic ending is one of the best ways a film can remain relevant in pop culture years after its release, and this tactic continues to be used to this day with films such as Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010) continually being dissected and discussed due to the nature of its ending.

Despite its gigantic amount of critical acclaim and it’s huge fanbase, Suspects does have a large number of critics. Roger Ebert himself was quite vocal on his tepid feelings of the film. When writing about the film’s ending on his website, Ebert wrote.

‘To the degree that you will want to see this movie, it will be because of the surprise, and so I will say no more, except to say that the "solution," when it comes, solves little - unless there is really little to solve, which is also a possibility.’

Here, Ebert seems to view the ending as little more than a gimmick meant to increase long term interest in a film that doesn’t really have much to say on its own. That the inconclusive nature of the ending is more a symptom of Singer’s inability to properly end the narrative rather than a genuine artistic decision. A flaw rather than a feature. This is a fairly common view that many viewers have towards open ended films, and it is a consequence of ending a film in such a way. In some cases, a cliffhanger can feel more like storytelling impotence rather than storytelling mastery.

Conclusive endings have the benefit of putting the entire audience on a level playing field. With more ambiguous endings, the audience's enjoyment of the film’s narrative hinges on their ability (or interest) in piercing the narrative together. Closed endings removes this issue, the entire audience is told the story at the same level and understand what happens identically. However this can lead to the issue of audience passivity, where the audience is not asked to engage their brain and so become disinterested in what they are watching. This is a complaint that has been aimed towards major Hollywood productions for decades, and the push against audience passivity was one of the motivating factors of the postmodernist film movement in the first place.

In conclusion, the ending of a film decides what the viewer will feel the moment the credits begin. Not only does the ending close the narrative, it also acts as the final thing the audience sees. By ending conclusively, a film can leave an audience feeling satisfied and complete, leaving them knowing that they have spent their money well. This works best in certain kinds of films, such as blockbusters and family films, which are highly competitive from a market perspective and need a satisfying conclusion to keep a broad group of viewers happy.

However, a conclusive ending will rarely keep the audience thinking. The more themes and plot threads that are kept in the air, the more likely the audience is to think about the film later down the line. The viewer becomes a part of the film, the narrative does not function without them, they have to engage with the text. Although an audience member may not feel as immediately satisfied with an open ended narrative, they may thank the filmmakers later on for giving them something to think about. Basically, it is a question of immediate gratification versus long term engagement, and this question exists entirely due to the nature of a film’s ending.

By Jack D. Phillips

Tuesday, 12 January 2016

'Horror'

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The Thing (1982)

There Will be Blood (2007)

Dragon ball Z (1989-1996)

Halloween (1978)

Game of Thrones (2011-)

The Babadook (2014)

Through a Glass Darkly (1963)

Boogie Nights (1997)

Return of the Living Dead (1985)

Stephen King's I.T (1990)

Carrie (1976)

Antichrist (2009)

Trainspotting (1996)

The Wicker Man (1973)

American Psycho (2000)

Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Attack on Titan (2013)

The Call of Cthulhu (1928)

Alien (1979)

Nosferatu (1922)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

When the Wind Blows (1986)

By Jack D. Phillips

A Zoom Film Collage

Tuesday, 5 January 2016

'Love'

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Avatar the Legend of Korra (2012)

Adventure Time (2010)

Boogie Nights (1997)

Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

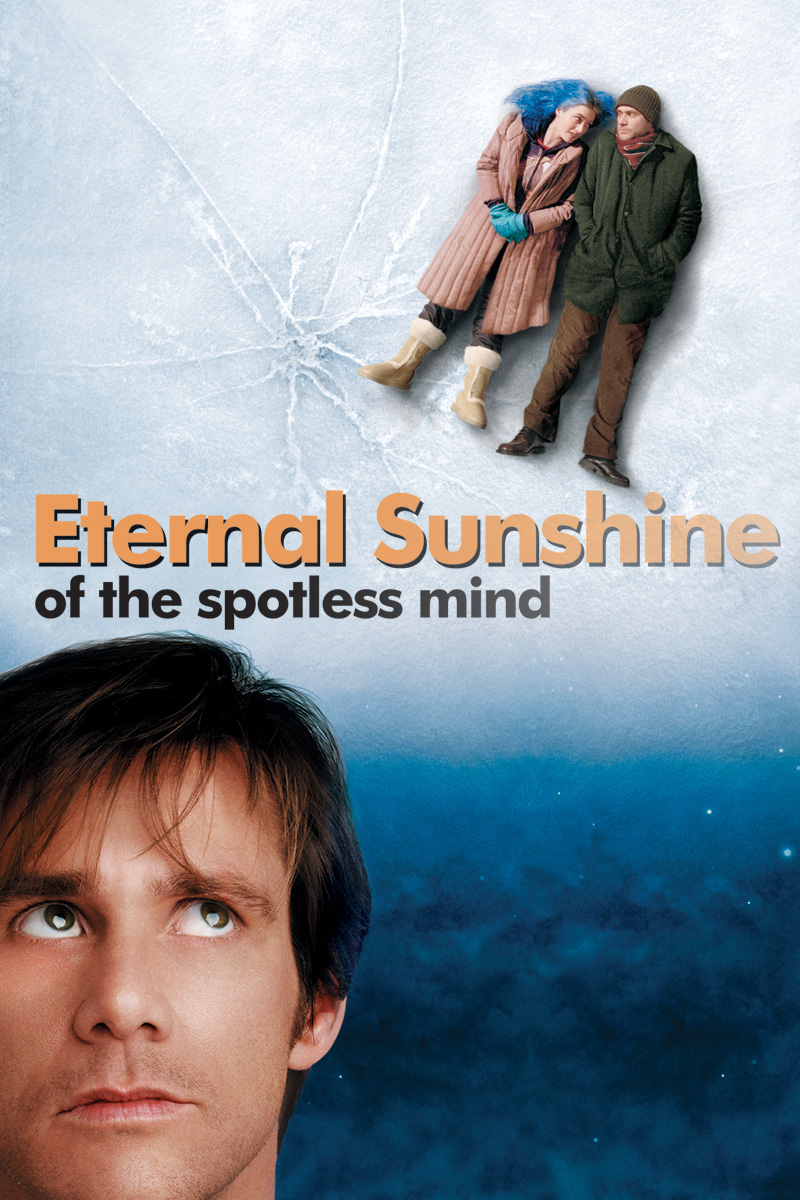

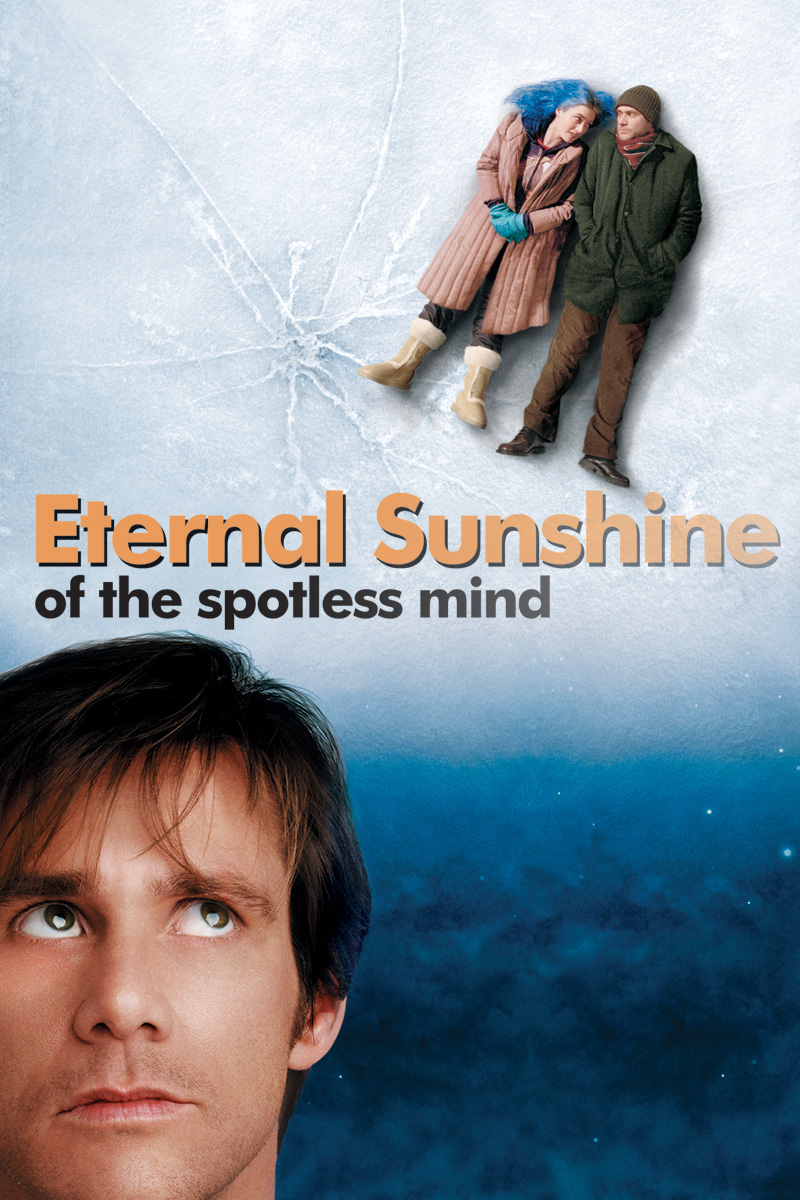

Eternal Sunshine of the Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Ed Wood (1994)

It's such a beautiful day (2012)

Ocean Waves (1993)

On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969)

5 Centimetres Per Second (2007)

Telltale's The Walking Dead (2012)

The Innocents (1963)

The Master (2012)

Carrie (1976)

Lost in Translation (2003)

Avatar the Last Airbender (2005)

The Slippery Slope (2003)

Pinocchio (1940)

Casino Royale (2006)

Casablanca (1942)

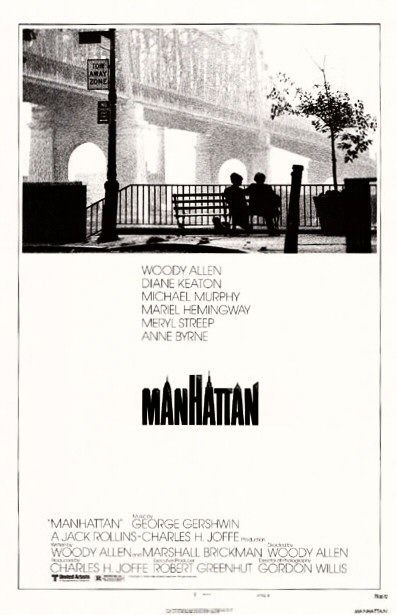

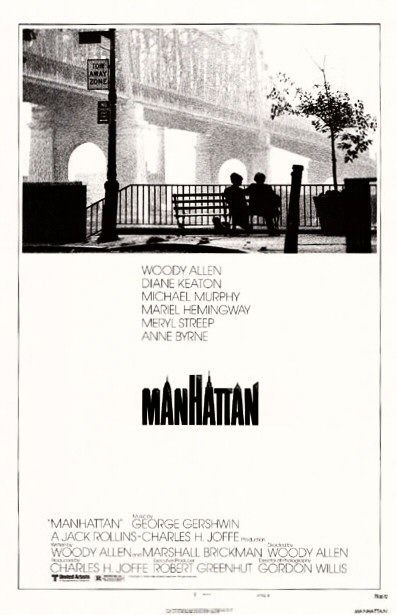

Manhattan (1979)

Return of the Jedi (1983)

Butch Cassidey and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Jack D. Phillips

A Zoom Film Collage

Film Collages 2.0

Hello everybody. I hope you all had a Merry Christmas.

One big change I want to occur on this blog in 2016 is an increase in technical proficiency on my part.

The many collages I released on the blog in the later months of 2015 were made by using Google docs and so were quite primitive and limited.

Over Christmas I purchased Adobe Photshop and so I will be using this to create a far more advanced and delicately made series of collages from this point on, with a greater amount of creative input and control on my part.

I hope you enjoy the better content.

By Jack D. Phillips

One big change I want to occur on this blog in 2016 is an increase in technical proficiency on my part.

The many collages I released on the blog in the later months of 2015 were made by using Google docs and so were quite primitive and limited.

Over Christmas I purchased Adobe Photshop and so I will be using this to create a far more advanced and delicately made series of collages from this point on, with a greater amount of creative input and control on my part.

I hope you enjoy the better content.

By Jack D. Phillips

Monday, 4 January 2016

Photography Reflective Journal (2)

Edited Pictures

Now I will discuss the various post production edits I have made to some of my photographs for the purposes of the course.

The first images I edited were done so on the online application Pixlr. The site, although basic in many respects, allows for a wide range of alterations to be made, from cropping to colour adjustments and so on. I chose to edit some pictures that I felt has interesting elements within them but were not fully realised.

The below images were all altered in drastically different ways and show a range of simple techniques to enhance their effects.

For the picture on top, I cropped a significant portion of the right side of the image so as to have less negative space distracting the viewer. I also added a shadowy blur to the left side, forcing the eye to the cat in the middle of the image. A few simple techniques to guide the viewers eye towards the most interesting part of the frame.

For the picture in the middle, I sharpened the image as much as possible without making the effect distracting and then desaturated the colour, giving it a washed out look. Finally I intensified the shadows, cropped a small section from the right side and cleaned up some unwanted blemishes. This was done to enhance the images creepy mood and atmosphere above what was originally possible.

Finally, the bottom image had the opposite effects as the one in the middle. The colour was intensified dramatically and a blur effect was given to the edges of the frame. The gave the image a bleeding effect and evoked a dreamlike fantasy of sorts.

I feel that all three images are improvements on the originals (I have provided them alongside for comparison) and are great examples of my use of editing in post. I also edited some pictures using Adobe Photoshop Elements, however those images were given far smaller and subtler changes, these images are the best examples I have of a photo being dramatically transformed and altered in post.

By Jack D. Phillips

Monday, 28 December 2015

Happy New Year!

Not a whole lot to say here, other than I hope that all you reading this have a great new year.

In 2016 I hope to expand and grow this blog further and grow into new forms of content. I love maintaining this little project and I hope I am able to for many more years to come.

HAPPY 2016 EVERYBODY!

By Jack D. Phillips

In 2016 I hope to expand and grow this blog further and grow into new forms of content. I love maintaining this little project and I hope I am able to for many more years to come.

HAPPY 2016 EVERYBODY!

By Jack D. Phillips

Thursday, 24 December 2015

Photography Reflective journal (1)

As part of the Academic and Contemporary Skill for Film and Media module on my university film course, I have been asked to write a reflective journal on my photography to demonstrate my progress and my thought process relating to my photography.

I decided I would like to give this journal in the form of blog posts so it can be publicly read.

Early Pictures

With my first few photos, I was interested in manipulating the aperture setting on my camera to distort and reduce the light in my images. I was interested in the moody and mysterious quality the gave otherwise mundane and unremarkable photographs.

|

| One of the first photographs I took with my DSLR camera. |

This is a common theme throughout my portfolio, with an abundance of underexposed and dimly lit images.

Although I have learned since these early images to not abuse the aperture settings excessively, I still enjoy the effect of these dim images and have come to consider them something of a signature of mine.

|

| Another early photograph demonstrating the low lighting I favoured at that time. |

Another characteristic throughout my earlier photos was an aversion to the 'auto' setting on my camera, particularly auto-flash. I have since incorporated more pictures using this setting, however early on basically every picture I took was taken in manual mode, due to me disliking the falseness of flash lighting and wanting to figure my new camera out for myself.

The last aspect of my early photos that I wish to comment on was my aversion to photographing people, preferring to shoot inanimate objects or scenery. This remains my preferred subject to this day, however I have taken steps to incorporating more portraits into my portfolio as per the requirements of the module assessments.

This concludes the first post in self-reflecting journal. More shall be released in the coming days.

By Jack D. Phillips

Sunday, 20 December 2015

Music in Film

Whiplash (2014)

Goldeneye (1995)

Watership Down (1976)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996)

One Froggy Morning (1955)

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

A Very Murray Christmas (2015)

Do the Right Thing (1989)

The Sound of Music (1965)

What's Opera Doc? (1957)

Perfect Blue (1997)

The Meaning of Life (2005)

O Brother Where Art Thou? (2000)

The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013)

Stop Making Sense (1984)

Jack D. Phillips

My 30 Favourite Films COMPLETE

To celebrate the one year anniversary of this blog, I will now list my favourite films of all time. I simply adore every film on this list from start to finish, and it was ridiculously hard to narrow it down to only thirty films.

Also, I have disqualified any film that I have not seen within at least two years, below are a the films that may have made it on here if not blocked by this rule.

M (1931)

Ikiru (1952)

Seven Samurai (1954)

The Godfather (1972)

The Wicker Man (1973)

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Raging Bull (1980)

Goodfellas (1990)

Battle Royale (2000)

Oldboy (2003)

There Will be Blood (2007)

Also a special mention has to go out to the film When the Wind Blows (1986), which is an unbelievable masterpiece in every way, however due to its incredibly bleak tone I cannot in any way claim to enjoy it. Do this depressing nature I also have no real desire to rewatch the film in the foreseeable future.

Aside from these honourable mentions, this is a collection of the greatest films ever made in my eyes, listed in chronological order.

My favourite film of the silent era, Sunrise is an intensly emotional and dreamlike experience. It uses very few title cards, telling its story entirely through its amazing visuals and its stunning soundtrack.

This is basically a film that I could watch any time any place, it goes through so many emotions so effortlessly and is a joy to wander through. In particular the Cathedral scene at around the 1/3 point in the film is one of the most overwhelming scenes in any film period.

This is basically a film that I could watch any time any place, it goes through so many emotions so effortlessly and is a joy to wander through. In particular the Cathedral scene at around the 1/3 point in the film is one of the most overwhelming scenes in any film period.

Citizen Kane (1941, Orson Welles)

What even needs to be said about this film? One of the most complex, stunningly structured and relatable character studies in the history of film. A towering achievement in every aspect of filmmaking, from early scripting to final editing and everything in between.

All wrapped up by one of the most powerful endings in film history.

Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder)

A dark and twisted little tale, filled with intrigue and brimming with character. One of the best constructed screenplays of all time without a doubt.

Slick, beautifully told, and able to balance many moving parts without ever feeling overwritten or difficult to follow. A joy of genre cinema.

Also, yet another exceptional ending scene, capping the films bleak mood and grim characterization.

Rashomon (1950, Akira Kurosawa)

I am not too concerned with giving any kind of ranking for this list, however I will be exceptional in this case. Rashomon is probably my favourite film ever made making the the number one film here.

From the very first shot this film captivated me, mysterious and engulfing. Truly my favourite opening of all time.

I love every aspect of this film, from it's genius screenplay, to its amazing performances (Tishiro Mifune is almost literally feral in this film), and the stunning cinematography.

Sheer beauty on celluloid.

Tokyo Story (1953, Yasujiro Ozu)

Ozu is a filmmaker that I am very cautious of. Mainly because I feel I could very easily become totally obsessed with him. His films embody and encapsulate the human spirit like few others, and his eye for detail is exquisite.

I plan on updating this list next year, and if I do expect a lot more Ozu to appear.

This film is simply gorgeous. Tender, solemn and brimming with dignity.

The Bad Sleep Well (1960, Akira Kurosawa)

The Bad Sleep Well (1960, Akira Kurosawa)

Yet another Japanese film, and another from director Akira Kurosawa. This is easily his most overlooked film, an incredibly crafted noire with some of the best performances and writing you will see in any thriller.

Psychologically challenging and heartbreaking by the end, with a lot of credit going to Toshiro Mifune, who is always incredible to behold.

Kurosawa took a screenplay loosely based on Hamlet and transformed it into something new and wonderful.

Persona (1966, Ingmar Bergman)

Easily the least accessible film on this list. Persona is disjointed, pretentious and obscure.

It is also revealing, daring and shows the great Bergman at the very heights of his powers. Things are done in this film that astonish me, and terrify me. Probably the sharpest and most daring film on this entire list.

Sadly this is the only Bergman film on the list, I had to be very picky and restrictive on that front. A true shame.

Kes (1969. Ken Loach)

One of the simplest films on the list, along with Tokyo Story. A simple look into the raw human experience of a boy in an impoverished environment.

Heartbreakingly real and filmed with expert care and attention.

Not a flashy film, but one that gives a window into another world, one of the things that films are amazing at doing.

F for Fake (1973, Orson Welles)

Where Citizen Kane started Welles' career with an incredibly told and beautifully crafted narrative masterpiece, this film ends his career on a less conventional note.

Where Citizen Kane started Welles' career with an incredibly told and beautifully crafted narrative masterpiece, this film ends his career on a less conventional note.

Totally non-linear, and without a any kinda of typical structure, yet still totally coherant and engrossing. A film in which every single cut sizzles and pops with interest and style, probably the most interesting documentary film I have ever seen.

Welles truly was an incredible artist, and despite his own self-deprecation in this film, totally worthy of the praise he is given.

Taxi Driver (1976, Martin Scorsese)

As of the time of writing this list, I have only just begun the process of rediscovering Martin Scorsese. Having watched (and loved) many of his film a fair while ago, I have begun to work my way back through his filmography with this film.

As of the time of writing this list, I have only just begun the process of rediscovering Martin Scorsese. Having watched (and loved) many of his film a fair while ago, I have begun to work my way back through his filmography with this film.

And hot damn it's amazing. Possibly the most beautiful depiction of an urban setting in the history of film, garnished by Bernard Hermann's beautiful and bold score, and anchored by the simply incredibly Robert De Niro.

It fascinates me how audiences must have reacted to this film back in the seventies. This must have seemed like a feral beast entering their multiplex.

Watership Down (1978, Martin Rosen)

The first animated film on this list and a truly beautiful one. One of the most emotionally complex films ever made, ranging from serine joy to jagged existential peril without any kind of inconsistencies in tone.

The first animated film on this list and a truly beautiful one. One of the most emotionally complex films ever made, ranging from serine joy to jagged existential peril without any kind of inconsistencies in tone.

Nature has never been so stunningly animated nor as characterised in its own right. You feel the personality of the countryside in this film.

Also, the sequence with Art Garfunkel's beautiful song 'Bright Eyes' is easily one of the greatest pairings of music and image I have ever seen.

Manhattan (1979, Woody Allen)

Manhattan (1979, Woody Allen)

It hard for me to describe why I love this film so much. When compared to Annie Hall (which was also considered for this list) this film is far less realistic in its depiction of love in the modern age, but I think it this shunning of realism that makes me love it so much.

Allen creates what might be the purest and most optimistic portrayal of romance that has ever been made, a story in which the message is simply to be with the person you love and screw what everyone thinks.

Beautifully photographed and scored with the excellent music of George Gerschwin. This is a film that is certainly in my sights for a rewatch soon.

The Elephant Man (1980, David Lynch)

I need to watch more of Lynch's incredible filmography, which is as terrifying to think of as it is exciting. The Elephant man is both delicate and sympathetic towards a very tragic historical figure, yet also harsh and ruthless when condemning the culture that caused this tragedy, and by extension our society.

I need to watch more of Lynch's incredible filmography, which is as terrifying to think of as it is exciting. The Elephant man is both delicate and sympathetic towards a very tragic historical figure, yet also harsh and ruthless when condemning the culture that caused this tragedy, and by extension our society.

One of the most visceral and invigorating period pieces ever made, and quiet possibly the most stunningly shot Black and White film I have ever seen (although the competition is certainly fierce in that area).

Just an incredible film.

Back to the Future (1985, Robert Zemeckis)

Although humble and small in comparison to the true filmmaking juggernauts I have showcased so far, this film is probably the most invigorating and fun examples of basic narrative cinema ever made. Fun and enjoyable in every single scene, and joyful to rewatch. Worthy of its status in pop culture.

Not much to say, other than everything was done to near perfection here. The quintessential recipe for telling a fun and adventurous story.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988, Isao Takahata)

I am going to try and keep this short. With the exception of When the Wind Blows and one or two other films later in the list, this film carries more emotional power over me than any other. I have a long history with this one.

Touching on every level, as emotionally complex as it is amazingly simple structure wise. Just watching two doomed characters trying to survive is more than enough on its own, and some scenes from this film hurt like a gun. Just, incredible.

Do the Right Thing (1989, Spike Lee)

I am trying so hard to not pun off this title, but this film truly does do the right thing. Funny, revealing and playful, this film looks at race in a way which is not preachy nor overly solemn. It blames everybody embroiled in the pointless conflict, showing wisdom well above the years of the young Spike Lee.

I am trying so hard to not pun off this title, but this film truly does do the right thing. Funny, revealing and playful, this film looks at race in a way which is not preachy nor overly solemn. It blames everybody embroiled in the pointless conflict, showing wisdom well above the years of the young Spike Lee.

Inventive and original in its style, this is a film that actually derives strength from being heavily dated, entrenching itself so firmly in its contemporary setting that it becomes more of a landmark in history than anything else.

Probably the greatest film on race issues that will ever be made, which won't stop hacks like Paul Haggis coming a few years later to try for themselves, with sadly greater success.

A beautifully shot and emotionally tender portrayal of the greatest tragedy in modern history. Spielberg directs this gigantic film with the care and delicacy that can only come from a director with his amount of experience. Not a single shot is wasted in this film, the craftsmanship is truly amazing.

A beautifully shot and emotionally tender portrayal of the greatest tragedy in modern history. Spielberg directs this gigantic film with the care and delicacy that can only come from a director with his amount of experience. Not a single shot is wasted in this film, the craftsmanship is truly amazing.

Aside from the the excellent direction, the performances are universally excellent, the soundtrack is one of the greatest I have ever heard, and the pacing beggars belief. Perhaps the most engaging three hour film ever made (although I would need to rewatch Seven Smaurai to confirm that).

Fargo (1996, The Coen Brothers)

The Coen's are such inventive filmmakers, I doubt that there is any genre that they could not turn there skills towards. This film in particular is one of the cleverest uses of the noir format, a charming and deeply subversive take on one of the most influential genres of all time.

The Coen's are such inventive filmmakers, I doubt that there is any genre that they could not turn there skills towards. This film in particular is one of the cleverest uses of the noir format, a charming and deeply subversive take on one of the most influential genres of all time.

The thing that makes this film so wonderful is its overall message and purpose. Despite their cynical worldview, the Coen's show an incredible optimism in this film, a belief in the good nature in humanity that comes though the main character (played by Francis Mcdormand) so incredibly strongly.

This is basically a film that makes me feel happy to be alive, through an amazing lead performance and some excellent writing from the Coen's.

Boogie Nights (1997, Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson is a shining god. Every single film I have seen of his has been a masterpiece. This film in particular is one of the most poignant and engaging multi-character epics I have ever seen, and proof positive that a great artist can make any subject compelling.

Paul Thomas Anderson is a shining god. Every single film I have seen of his has been a masterpiece. This film in particular is one of the most poignant and engaging multi-character epics I have ever seen, and proof positive that a great artist can make any subject compelling.

Within the confines of the California porn industry during the late seventies/early eighteen PTA fills his story with humour, tragedy, heartbreak and heart. In terms of sheer strength of narrative, this is one of the absolute greatest films I have ever seen.

Also, the performances and dialogue are both incredible across the board.

The Big Lebowski (1998, The Coen Brothers)

The most quotable film ever made. Just...beyond fascinating in every way, I just want to dissect this film and rewatch it endlessly because absolutely everything about its frantic and wild story is spot-on perfect. Not a single scene fails to connect, and I genuinely think I could watch this film on an endless loop.

I don't even think I can articulate this film any further, it has just become a part of me in a way that no other film has.

I adore films that are able to turn their settings into breathing characters, and this film is one of the strongest examples of this that I can think of.

A beautifully told story, topped off with one of the best climaxes in any animated film.

This film is hard to talk about. It has more power over than any other film I can think about, with simple images and sounds from the film being able to reduce me to putty.

If Rashomon isn't my favourite film then it has to be this one, I simply adore everything about it. From Charlie Kaufman's utterly perfect script, to the stunning and heart wrenching script, to the amazing performances from the entire cast. Everything in this film works. Even the soundtrack, quite possibly my favourite soundtrack of all time, can reduce me to a whimpering fool if I am exposed to it for too long.

To sum up my feelings for this film, I was once so enraptured by it that I watched it twice, back-to-back, in one night.

Enter the Void (2010, Gasper Noe)

One of the most ambitious and gloriously pretentious projects in the history of cinema, yet despite it's pretensions it is able to tap into something very human and touching.

A true technical triumph in both the craft of film, and the art of cinema.

It's Such a Beautiful Day (2012, Don Hertzfelt)

Don Hertzfelt is easily my favourite film maker working today. I can't do his work anywhere near justice in words so I can only beg you to watch some of his short films, easily available on Youtube. Seriously, get out of here, go now.

Don Hertzfelt is easily my favourite film maker working today. I can't do his work anywhere near justice in words so I can only beg you to watch some of his short films, easily available on Youtube. Seriously, get out of here, go now.

If you want to hear what I think about his (currently) only feature film, here it is. It is basically the antithesis of Enter the Void. Not pretentious or technically extravagant in any way, the main character is a damn stick-figure for christ's sake! However the film still manages to be one of the most touching things I have ever seen, and Hertzfelt does things that I have never seen before in my life with some basic B/W photography and some line drawings. In fact, this is another film that manages to contest Rashomon as my favourite feature film of all time.

I am utterly obsessed with Hertzfelt, and if there is a single artist on this list that I recommend you check out it has to be this one.

Paul Thomas Anderson, after showing total mastery over conventional storytelling in films like Boogie Nights, dives into the wild and experimental with this film. The Master is unconventional and without a clear structure, but it is far from aimless or unfocused.

The film tells the story of two men and the nature of their complex relationship, along with looking at ideas of faith and destiny. The film is complex and brainfrying but slow and relaxed enough to wash over the viewer. I hate using this term too much because I feel it gets thrown around a lot, but this film is truly an incredible experience.

A Field in England (2013, Ben Wheatley)

Easily the least accessible and hardest to describe film on this list. A Field in England is a drugged out and alienating experience, dripping in horror and comedy alike.

Easily the least accessible and hardest to describe film on this list. A Field in England is a drugged out and alienating experience, dripping in horror and comedy alike.

Basically, there is not a single other film on this list that comes even close to this films strangeness, yet its power is incredible. The film chills, amuses and utterly horrifies, there are moments from this film that are truly burnt into my memory.

Just, tread carefully with this one.

Her (2013, Spike Jonze)

Spike Jonze interests me. I would personally consider the first two films Jonze directed to be less attributable to Jonze himself and more screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (who also wrote Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). So when their collaboration ended in the early 2000's, it would be reasonable to assume that Spike Jonze would slip away.

Spike Jonze interests me. I would personally consider the first two films Jonze directed to be less attributable to Jonze himself and more screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (who also wrote Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). So when their collaboration ended in the early 2000's, it would be reasonable to assume that Spike Jonze would slip away.

However he then comes along with this utter masterpiece, a film so sweeping and intense in it's emotions and so utterly stunning in its visuals that it takes my breath away to even think about. I am deeply sorry for any dismissiveness I or anyone else may have had towards you Spike Jonze.

And an extra mention has to go to Arcade Fire (A band I really like) for creating the best soundtrack in a film in recent years.

Oh, this alongside The Master transformed Joaquin Pheonix into possibly my favourite living actor. He is just incredible.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013, Isao Takahata)

Isao Takahata is one of the all time unsung heroes of animation. I love every single thing about this film, to the point where I don't really want to write about it. Just please see it, please. I have never cared more for a character in my life, by the end of this film I was literally screaming internally for things to turn out ok for Kaguya.

Isao Takahata is one of the all time unsung heroes of animation. I love every single thing about this film, to the point where I don't really want to write about it. Just please see it, please. I have never cared more for a character in my life, by the end of this film I was literally screaming internally for things to turn out ok for Kaguya.

Possibly the most beautiful looking film ever made, and dripping with the things that make me love film. Emotion, beauty, poetic storytelling. There is probably no film on this list that I want to be seen more, especially considering that it is the unfortunate swansong to the greatest studio in animation history.

Inside Out (2015, Pete Doctor, Ronnie Del Carmen)

Pixar is a strange entity in the world of animation. Incredibly talented, both artistically and technically, yet somehow a little cold. There is something a little detached and anonymous about them when compared to a studio like Ghibli or even plain old Disney.

Pixar is a strange entity in the world of animation. Incredibly talented, both artistically and technically, yet somehow a little cold. There is something a little detached and anonymous about them when compared to a studio like Ghibli or even plain old Disney.

Inside Out blew me away however, and represents the biggest leap I could have possibly have hoped for the studio. A film as psychosocially intelligent as it is visually stunning, just mindblowing to see on the big screen.

There are films which genuinely have the power to change the world, and that's what I want Inside Out to do. I want, no, demand that the way society views animation (and film on the whole) matures. We need to challenge ourselves in art or we will begin to roll backwards. I believe Inside Out represents a way forward, and with its success, maybe animation will be used for more in the west than a thing to distract children.

Seven Samurai (1954, Akira Kurosawa)

This film is every bit as good as everybody says it is. One of the most remarkable examples of how to develop a large number of characters and frame them against some of the most engaging action ever put to celluloid.

This film is every bit as good as everybody says it is. One of the most remarkable examples of how to develop a large number of characters and frame them against some of the most engaging action ever put to celluloid.

Truly some of the best cinematography and some of the best performances you will see in Japanese film. Just a shame that I waited until midway through making this list to rewatch this masterpiece. I could watch this film literally a hundred times and still find it fresh and new, it's alive.

Stop Making Sense (1984, Jonathan Demme)

One of the most surprising films I have ever seen. It is hard to imagine that a simple concert film (literally, there is nothing to the film other than just a concert) could be this good. The Talking Heads' music, the editing and the overall pace are all exquisite.

One of the most surprising films I have ever seen. It is hard to imagine that a simple concert film (literally, there is nothing to the film other than just a concert) could be this good. The Talking Heads' music, the editing and the overall pace are all exquisite.

I honestly am floored by this one, a week after watching it and I can't stop listening to it (I am listening to Once in a Lifetime as I write this sentence) and it keeps drawing my attention from other things. Just, incredible in every single way.

Through a Glass Darkly (1961, Ingmar Bergman)

Still, Harriet Anderson gives one of the greatest performances I have ever seen in this film and the entire cast does incredible work. Bergman offers an intelligent and emotionally charged portrait of a crumbling family and doesn't hold back in a single scene. Just an incredible drama.

The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton)

This is film that I think I reject not putting on the list the most. I have no real reason for the exclusion and although I cannot think of any film in particular that I would have cycled out for this one, it does play heavily on my mind.

This is film that I think I reject not putting on the list the most. I have no real reason for the exclusion and although I cannot think of any film in particular that I would have cycled out for this one, it does play heavily on my mind.

Anyway, this is probably the most unnerving and unsettling horror film I have ever seen, and one of the most amazingly edited films period. It is a feature length session of build-up that finally results in one of the most crushing notes of any film I have ever seen.

This is the kind of film I feel you could spend many a year pouring over and deconstructing, finding new and horrifying things the entire time.

The Thing (1982, John Carpenter)

A film that I have watched many a time and have left with something new on each viewing. Horror, joy, fascination, it is a film that has given me much. Carpenter was truly an incredible director in his prime, and is one of the most diverse filmmakers in history.

With this film Carpenter achieved something greater than almost every other film on the planet has, impact. True impact, the kind that sends ripples and affects things that one would not expect. I assure you that every other film featuring a parasite or an desolate environment owes this film a true debt. A film that has influenced me very heavily indeed.

Also, I have disqualified any film that I have not seen within at least two years, below are a the films that may have made it on here if not blocked by this rule.

M (1931)

Ikiru (1952)

Seven Samurai (1954)

The Godfather (1972)

The Wicker Man (1973)

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Raging Bull (1980)

Goodfellas (1990)

Battle Royale (2000)

Oldboy (2003)

There Will be Blood (2007)

Also a special mention has to go out to the film When the Wind Blows (1986), which is an unbelievable masterpiece in every way, however due to its incredibly bleak tone I cannot in any way claim to enjoy it. Do this depressing nature I also have no real desire to rewatch the film in the foreseeable future.

Aside from these honourable mentions, this is a collection of the greatest films ever made in my eyes, listed in chronological order.

Sunrise (1927, F.W Murnau)

My favourite film of the silent era, Sunrise is an intensly emotional and dreamlike experience. It uses very few title cards, telling its story entirely through its amazing visuals and its stunning soundtrack.

Citizen Kane (1941, Orson Welles)

What even needs to be said about this film? One of the most complex, stunningly structured and relatable character studies in the history of film. A towering achievement in every aspect of filmmaking, from early scripting to final editing and everything in between.

All wrapped up by one of the most powerful endings in film history.

Double Indemnity (1944, Billy Wilder)

A dark and twisted little tale, filled with intrigue and brimming with character. One of the best constructed screenplays of all time without a doubt.

Slick, beautifully told, and able to balance many moving parts without ever feeling overwritten or difficult to follow. A joy of genre cinema.

Also, yet another exceptional ending scene, capping the films bleak mood and grim characterization.

Rashomon (1950, Akira Kurosawa)

I am not too concerned with giving any kind of ranking for this list, however I will be exceptional in this case. Rashomon is probably my favourite film ever made making the the number one film here.

From the very first shot this film captivated me, mysterious and engulfing. Truly my favourite opening of all time.

I love every aspect of this film, from it's genius screenplay, to its amazing performances (Tishiro Mifune is almost literally feral in this film), and the stunning cinematography.

Sheer beauty on celluloid.

Tokyo Story (1953, Yasujiro Ozu)

Ozu is a filmmaker that I am very cautious of. Mainly because I feel I could very easily become totally obsessed with him. His films embody and encapsulate the human spirit like few others, and his eye for detail is exquisite.

I plan on updating this list next year, and if I do expect a lot more Ozu to appear.

This film is simply gorgeous. Tender, solemn and brimming with dignity.

Yet another Japanese film, and another from director Akira Kurosawa. This is easily his most overlooked film, an incredibly crafted noire with some of the best performances and writing you will see in any thriller.

Psychologically challenging and heartbreaking by the end, with a lot of credit going to Toshiro Mifune, who is always incredible to behold.

Kurosawa took a screenplay loosely based on Hamlet and transformed it into something new and wonderful.

Persona (1966, Ingmar Bergman)

Easily the least accessible film on this list. Persona is disjointed, pretentious and obscure.

It is also revealing, daring and shows the great Bergman at the very heights of his powers. Things are done in this film that astonish me, and terrify me. Probably the sharpest and most daring film on this entire list.

Sadly this is the only Bergman film on the list, I had to be very picky and restrictive on that front. A true shame.

Kes (1969. Ken Loach)

One of the simplest films on the list, along with Tokyo Story. A simple look into the raw human experience of a boy in an impoverished environment.

Heartbreakingly real and filmed with expert care and attention.

Not a flashy film, but one that gives a window into another world, one of the things that films are amazing at doing.

F for Fake (1973, Orson Welles)

Totally non-linear, and without a any kinda of typical structure, yet still totally coherant and engrossing. A film in which every single cut sizzles and pops with interest and style, probably the most interesting documentary film I have ever seen.

Welles truly was an incredible artist, and despite his own self-deprecation in this film, totally worthy of the praise he is given.

Taxi Driver (1976, Martin Scorsese)

And hot damn it's amazing. Possibly the most beautiful depiction of an urban setting in the history of film, garnished by Bernard Hermann's beautiful and bold score, and anchored by the simply incredibly Robert De Niro.

It fascinates me how audiences must have reacted to this film back in the seventies. This must have seemed like a feral beast entering their multiplex.

Watership Down (1978, Martin Rosen)

The first animated film on this list and a truly beautiful one. One of the most emotionally complex films ever made, ranging from serine joy to jagged existential peril without any kind of inconsistencies in tone.

The first animated film on this list and a truly beautiful one. One of the most emotionally complex films ever made, ranging from serine joy to jagged existential peril without any kind of inconsistencies in tone.Nature has never been so stunningly animated nor as characterised in its own right. You feel the personality of the countryside in this film.

Also, the sequence with Art Garfunkel's beautiful song 'Bright Eyes' is easily one of the greatest pairings of music and image I have ever seen.

Manhattan (1979, Woody Allen)

Manhattan (1979, Woody Allen)It hard for me to describe why I love this film so much. When compared to Annie Hall (which was also considered for this list) this film is far less realistic in its depiction of love in the modern age, but I think it this shunning of realism that makes me love it so much.

Allen creates what might be the purest and most optimistic portrayal of romance that has ever been made, a story in which the message is simply to be with the person you love and screw what everyone thinks.

Beautifully photographed and scored with the excellent music of George Gerschwin. This is a film that is certainly in my sights for a rewatch soon.

The Elephant Man (1980, David Lynch)

One of the most visceral and invigorating period pieces ever made, and quiet possibly the most stunningly shot Black and White film I have ever seen (although the competition is certainly fierce in that area).

Just an incredible film.

Back to the Future (1985, Robert Zemeckis)

Although humble and small in comparison to the true filmmaking juggernauts I have showcased so far, this film is probably the most invigorating and fun examples of basic narrative cinema ever made. Fun and enjoyable in every single scene, and joyful to rewatch. Worthy of its status in pop culture.

Not much to say, other than everything was done to near perfection here. The quintessential recipe for telling a fun and adventurous story.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988, Isao Takahata)

I am going to try and keep this short. With the exception of When the Wind Blows and one or two other films later in the list, this film carries more emotional power over me than any other. I have a long history with this one.

Touching on every level, as emotionally complex as it is amazingly simple structure wise. Just watching two doomed characters trying to survive is more than enough on its own, and some scenes from this film hurt like a gun. Just, incredible.

Do the Right Thing (1989, Spike Lee)

I am trying so hard to not pun off this title, but this film truly does do the right thing. Funny, revealing and playful, this film looks at race in a way which is not preachy nor overly solemn. It blames everybody embroiled in the pointless conflict, showing wisdom well above the years of the young Spike Lee.

I am trying so hard to not pun off this title, but this film truly does do the right thing. Funny, revealing and playful, this film looks at race in a way which is not preachy nor overly solemn. It blames everybody embroiled in the pointless conflict, showing wisdom well above the years of the young Spike Lee.Inventive and original in its style, this is a film that actually derives strength from being heavily dated, entrenching itself so firmly in its contemporary setting that it becomes more of a landmark in history than anything else.

Probably the greatest film on race issues that will ever be made, which won't stop hacks like Paul Haggis coming a few years later to try for themselves, with sadly greater success.

Schindler's List (1993, Steven Spielberg)

Aside from the the excellent direction, the performances are universally excellent, the soundtrack is one of the greatest I have ever heard, and the pacing beggars belief. Perhaps the most engaging three hour film ever made (although I would need to rewatch Seven Smaurai to confirm that).

Fargo (1996, The Coen Brothers)

The thing that makes this film so wonderful is its overall message and purpose. Despite their cynical worldview, the Coen's show an incredible optimism in this film, a belief in the good nature in humanity that comes though the main character (played by Francis Mcdormand) so incredibly strongly.

This is basically a film that makes me feel happy to be alive, through an amazing lead performance and some excellent writing from the Coen's.

Boogie Nights (1997, Paul Thomas Anderson)

Within the confines of the California porn industry during the late seventies/early eighteen PTA fills his story with humour, tragedy, heartbreak and heart. In terms of sheer strength of narrative, this is one of the absolute greatest films I have ever seen.

Also, the performances and dialogue are both incredible across the board.

The Big Lebowski (1998, The Coen Brothers)

The most quotable film ever made. Just...beyond fascinating in every way, I just want to dissect this film and rewatch it endlessly because absolutely everything about its frantic and wild story is spot-on perfect. Not a single scene fails to connect, and I genuinely think I could watch this film on an endless loop.

I don't even think I can articulate this film any further, it has just become a part of me in a way that no other film has.

Tokyo Godfathers (2003, Satoshi Kon)

A fast, wild and totally engrossing comedic-adventure. A masterpiece of an animated film which manages to combine the amusing antics of a film like Blues Brothers with deep and touching character and heart.

I adore films that are able to turn their settings into breathing characters, and this film is one of the strongest examples of this that I can think of.

A beautifully told story, topped off with one of the best climaxes in any animated film.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

(2004, Michel Gondry)

This film is hard to talk about. It has more power over than any other film I can think about, with simple images and sounds from the film being able to reduce me to putty.

If Rashomon isn't my favourite film then it has to be this one, I simply adore everything about it. From Charlie Kaufman's utterly perfect script, to the stunning and heart wrenching script, to the amazing performances from the entire cast. Everything in this film works. Even the soundtrack, quite possibly my favourite soundtrack of all time, can reduce me to a whimpering fool if I am exposed to it for too long.

To sum up my feelings for this film, I was once so enraptured by it that I watched it twice, back-to-back, in one night.

Enter the Void (2010, Gasper Noe)

This film kind of scares me a little. It is a voyage into a a dark, dirty and blurry world which does not hold back in any way.

One of the most ambitious and gloriously pretentious projects in the history of cinema, yet despite it's pretensions it is able to tap into something very human and touching.

A true technical triumph in both the craft of film, and the art of cinema.

It's Such a Beautiful Day (2012, Don Hertzfelt)

If you want to hear what I think about his (currently) only feature film, here it is. It is basically the antithesis of Enter the Void. Not pretentious or technically extravagant in any way, the main character is a damn stick-figure for christ's sake! However the film still manages to be one of the most touching things I have ever seen, and Hertzfelt does things that I have never seen before in my life with some basic B/W photography and some line drawings. In fact, this is another film that manages to contest Rashomon as my favourite feature film of all time.

I am utterly obsessed with Hertzfelt, and if there is a single artist on this list that I recommend you check out it has to be this one.

The Master (2012, Paul Thomas Anderson)

Paul Thomas Anderson, after showing total mastery over conventional storytelling in films like Boogie Nights, dives into the wild and experimental with this film. The Master is unconventional and without a clear structure, but it is far from aimless or unfocused.

The film tells the story of two men and the nature of their complex relationship, along with looking at ideas of faith and destiny. The film is complex and brainfrying but slow and relaxed enough to wash over the viewer. I hate using this term too much because I feel it gets thrown around a lot, but this film is truly an incredible experience.

A Field in England (2013, Ben Wheatley)

Basically, there is not a single other film on this list that comes even close to this films strangeness, yet its power is incredible. The film chills, amuses and utterly horrifies, there are moments from this film that are truly burnt into my memory.

Just, tread carefully with this one.

Her (2013, Spike Jonze)

Spike Jonze interests me. I would personally consider the first two films Jonze directed to be less attributable to Jonze himself and more screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (who also wrote Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). So when their collaboration ended in the early 2000's, it would be reasonable to assume that Spike Jonze would slip away.

Spike Jonze interests me. I would personally consider the first two films Jonze directed to be less attributable to Jonze himself and more screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (who also wrote Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). So when their collaboration ended in the early 2000's, it would be reasonable to assume that Spike Jonze would slip away.However he then comes along with this utter masterpiece, a film so sweeping and intense in it's emotions and so utterly stunning in its visuals that it takes my breath away to even think about. I am deeply sorry for any dismissiveness I or anyone else may have had towards you Spike Jonze.

And an extra mention has to go to Arcade Fire (A band I really like) for creating the best soundtrack in a film in recent years.

Oh, this alongside The Master transformed Joaquin Pheonix into possibly my favourite living actor. He is just incredible.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013, Isao Takahata)

Possibly the most beautiful looking film ever made, and dripping with the things that make me love film. Emotion, beauty, poetic storytelling. There is probably no film on this list that I want to be seen more, especially considering that it is the unfortunate swansong to the greatest studio in animation history.

Inside Out (2015, Pete Doctor, Ronnie Del Carmen)

Inside Out blew me away however, and represents the biggest leap I could have possibly have hoped for the studio. A film as psychosocially intelligent as it is visually stunning, just mindblowing to see on the big screen.

There are films which genuinely have the power to change the world, and that's what I want Inside Out to do. I want, no, demand that the way society views animation (and film on the whole) matures. We need to challenge ourselves in art or we will begin to roll backwards. I believe Inside Out represents a way forward, and with its success, maybe animation will be used for more in the west than a thing to distract children.

To finish off my anniversary look at my favourite films, here are five honourable mentions. The first two films on this list are films that I watched while uploading the list itself, and would have definitely been up for consideration if I had gotten to them sooner. The other films are ones that almost made it on, but I decided against it for one reason or another.

Seven Samurai (1954, Akira Kurosawa)

Truly some of the best cinematography and some of the best performances you will see in Japanese film. Just a shame that I waited until midway through making this list to rewatch this masterpiece. I could watch this film literally a hundred times and still find it fresh and new, it's alive.

Stop Making Sense (1984, Jonathan Demme)

I honestly am floored by this one, a week after watching it and I can't stop listening to it (I am listening to Once in a Lifetime as I write this sentence) and it keeps drawing my attention from other things. Just, incredible in every single way.

Through a Glass Darkly (1961, Ingmar Bergman)

I excluded this film purely because next to the complex majesty of Persona this far simpler Bergman film cannot help but look a little modest and unremarkable.

Still, Harriet Anderson gives one of the greatest performances I have ever seen in this film and the entire cast does incredible work. Bergman offers an intelligent and emotionally charged portrait of a crumbling family and doesn't hold back in a single scene. Just an incredible drama.

The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton)

Anyway, this is probably the most unnerving and unsettling horror film I have ever seen, and one of the most amazingly edited films period. It is a feature length session of build-up that finally results in one of the most crushing notes of any film I have ever seen.

This is the kind of film I feel you could spend many a year pouring over and deconstructing, finding new and horrifying things the entire time.

The Thing (1982, John Carpenter)

A film that I have watched many a time and have left with something new on each viewing. Horror, joy, fascination, it is a film that has given me much. Carpenter was truly an incredible director in his prime, and is one of the most diverse filmmakers in history.

With this film Carpenter achieved something greater than almost every other film on the planet has, impact. True impact, the kind that sends ripples and affects things that one would not expect. I assure you that every other film featuring a parasite or an desolate environment owes this film a true debt. A film that has influenced me very heavily indeed.

By Jack D. Phillips

A Zoom Film List

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)